The Waste

Emergency

We advocate for the recognition of the Waste Emergency - like the Climate and Ecological Emergency it's part of

What happens to UK waste?

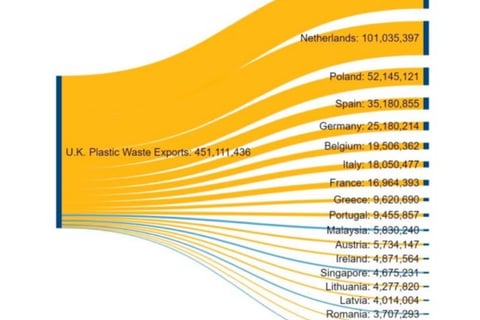

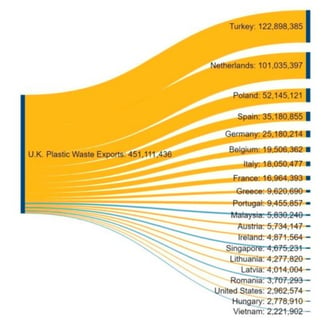

The UK exports over 60% of its plastic waste abroad. And that’s a lot – we produce up to 2.5m tonnes of plastic packaging waste a year.

But this is just packaging waste. Household waste, including non-plastics, is circa 27m tonnes per annum, and commercial and industrial waste is upward of 30m tonnes per annum.

In 2019 the UK had a missing 900,000 tonnes of plastic packaging, unaccounted for at end of life. This is presumably mismanaged, criminally or recklessly, and then lost to waste trafficking (illegally selling on waste), or in the environment.

Calls to ban plastic waste exports, including in the government’s own Skidmore report in 2023, and from Greenpeace, have not been agreed to by the government.

More of the waste the UK can’t manage goes to Turkey than to any other country. Polyethylene makes up 94% of the plastic waste which the UK exports to Turkey and 74% of all plastic waste Turkey receives.

A Greenpeace investigation has revealed that over 50% of recycling sent to Turkey cannot be recycled. It found waste being dumped and burned at the roadside.

Where does the rest of the world’s waste go?

“There are eight billion tonnes of plastic in the world – to put that into context, it weighs more than every single person who has ever existed.”

https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/news/mps-and-sheffield-researchers-call-ban-all-plastic-waste-exports

Much waste is is exported to southeast Asian countries and Turkey, where little is recycled. Mismanagement is estimated at 57% in Malaysia, and as much as 75% and 83% in Thailand and Indonesia respectively.

SE Asia is a hotspot for waste because it can be brought on international vessels returning from the West to China.

In 2018 China banned import of most plastics. This fundamentally changed the dynamic between nations, sharpening the international waste crisis by displacing an estimated 111m metric tons of plastic waste between 2021 and 2030.

It’s not just packaging

We use so many plastic products that have no good disposal method. Just one example among thousands is car tyres. Tonnes of these are taken every month to India and other countries to be pyrolysed - made into dirty, dirt-cheap fuel. This results in toxic emissions, especially in places where industrial standards are low.

If tyres aren’t pyrolized for cheap fuel or made into building materials or ground up for children’s playgrounds, they end up on huge dumps, often in the Middle East and Africa. These are huge fire risks and potential carbon bombs, as we have seen many times over the last half century.

But it's not just tyres. There are so many different plastic waste streams (amongst the most overlooked are carpets and hospital disposables).

Too complex to sort

It's not just the amount of stuff, either, but its complexity. Because plastics are often mixed, moulded, bonded to other materials, or even added intentionally to the environment, they are often impossible to separate economically, or to find recycling end markets for. This is one more reason that recycling will never, ever work on the scale we'd need it to, and can only amplify the existing problem by feeding degraded feedstock back into the recycling loop.

Illegal Trade in Plastics

So there is a huge discrepancy between the amount of plastic waste being exported and the capacities of importing countries to deal with it.

This has opened up a vast market for the trafficking of plastic. In the EU the estimated value of the criminal market is up to 15bn euros. Many of the countries that receive the most waste also have the biggest problem in illegal activity related to it: countries in East Asia, as well as India and Turkey. INTERPOL says organised crime is increasingly involved in illegal waste trade.

[Source: https://eia-international.org/wp-content/uploads/EIA-The-Truth-Behind-Trash-FINAL.pdf]

Planetary and Health Consequences

As we have seen, there is a global trade in plastic waste. This involves both legal and illegal routes.

Whether waste is legally traded or trafficked, its direction of travel is away from richer countries including the UK towards poorer countries.

There, it is illegally dumped and burned. It is legally recycled, but this, too, increases microplastics and the toxicity of waterways.

With fewer resources for cleanups and to fight for the rights to clean environments, many people are now living in the permanent backwash of the developed world’s plastic waste.

What is Waste Colonialism?

The term was first used at the 1989 UNEP Basel Convention.

It is the domination of one country by another, in which the richer country disposes of or dumps its waste using the poorer country’s land and resources. It is quite clear that, due to the impossibility of dealing with our plastic waste, the UK (and many of its rich international partners) have become waste colonialists.

Consequences and Solutions

Poisoned rivers and seas, soils contaminated with microplastics and plasticisers, polluted airways and nanoplastics in the blood... In the global context, nobody wins from this horrific state of affairs. But the poorest are the first losers.

In its consequences, then, the Waste Emergency mimics the action of the global Climate and Ecological Emergency (CEE), which the UK declared in 2019. Indeed, the Waste Emergency is a recognisable component of the overal CEE, both contributing to ecosystem collapse and to emissions in a tangible way. Even if we ever deal with our current plastic production, its backlog will continue to degrade and emit greenhouse gases over centuries.

Solutions are not obvious from our position in the eye of the raging waste storm. But it is clear that to mistake any temporary calm we enjoy in rich, Western countries, is to ignore reality at our peril. Our suggestion is to incorporate the Waste Emergency, which is also documented widely, into a recognition of the broader crisis whose existence is now fully proven.